Nepal’s grassroots communities charting sustainable futures

As a state that attained democracy only very recently in the 90’s, Nepal has been through various tumultuous political shifts—the end of a monarchy, a decade long Maoist people’s war, the mainstreaming of leftist movements, and neoliberalism to name a few. What particularly struck me was the large presence of the global development and foreign aid industry that has overshadowed Nepal for decades. Nepal has a very high concentration of NGOs that channel aid and services to the population. Nepali activists note that much of the development work in Nepal is a response to aid, funding, and external agendas rather than the needs of communities.

So when our Global South partners organized the “Rethinking Development” conference to question this very top-down development agenda so prominent in the country, it was quite significant given the context of Nepal. They brought together a diverse group of local peoples and deliberated over a bottom-up vision of wellbeing.

Over the course of our stay in Nepal, we visited some of the exciting work being done by our partners. Rather than deliver services to supposedly passive local populations, they were strengthening local institutions, building women’s collectives, and generating their own resources to improve their livelihoods in a sustainable way.

Below follows a photo-essay showcasing the bottom-up approaches of our partners in Nepal addressing everything from economic development to the climate crisis.

Photo: Digo Bikas Institute

Participants at the Rethinking development forum. The conference brought together several organizations such as women’s cooperatives, youth climate networks, citizens movements, forest researchers, peasant movement members, as well as some provincial government officials.

Photo: Ashlesha Khadse

Visit to a furniture factory funded by the Nari Chetana Kendra (WACN) credit society in Karve district.

WACN is one of the largest federations of women’s credit cooperatives in Nepal. It brings together small groups of women who pool their resources for building financial autonomy.

“There was a time when women had to go to a money lender with utensils as collateral to borrow even a dollar,” said a WACN leader. After the establishment of WACN’s women’s savings groups, women have been able to take part in various income generating activities and have access to credit. WACN’s women-led cooperatives now deal with large sums—up to 4 million USD.

Pictured above is a couple seated in front of their furniture factory, surrounded by other women members of WACN. The couple described their humble origins, and how they improved their material condition after the wife, who became a WACN member, was able to access credit to set up a furniture factory. Their factory now employs several others and is doing very well.

Photo: Ashlesha Khadse

A furniture factory supported by WACN members.

WACN members expressed that women’s control over finances didn’t only support their own needs, but also funded several men’s and family run businesses in the community.

These groups did not only serve to save money, the cooperatives turned into spaces for women to build confidence, enhance learning, engage in solidarity work, fight for their rights and against violence. Importantly, they undertook many group efforts to create sustainable livelihoods, such as agroecology to fight climate change.

Photo: Ashlesha Khadse

Photo: Digo Bikas Institute

Deepa [pictured to the left] , a self-taught farmer, standing at the edge of her farm. After joining WACN’s women’s group, she strengthened her skills though trainings offered in agroecological farming. Along with other members of her family, she grows many vegetables and farms fish.

“I am content that we can grow for most of my large families food needs from our own farm. We also sell to the market and make an additional income,” said Deepa.

Another WACN member [pictured to the right] observing Deepa’s farm.

Photo: Ashlesha Khadse

Despite their success, women’s credit cooperatives in Nepal, like WACN, are under serious threat due to a new law that inadvertently forces mergers between men and women’s cooperatives.

The government now requires a minimum limit of 500 people to one cooperative in rural areas, 2000 persons in semi-rural areas, and 5000 members in urban areas. However, most women’s cooperatives in rural areas are small with low numbers. WACN’s cooperatives range from 50 to 1,000, depending on the area. The new law forces women’s cooperatives to recruit new members meaning they will have to merge with other larger cooperatives.Most of those cooperatives are led by men. Many WACN members are concerned that women will become overshadowed if they are absorbed into men’s cooperatives. They will lose their autonomy, identity, and their ability to direct their organization as they want.

WACN is vocally opposing this law. Prativa Subedi, the founder of WACN says, “The basic idea of cooperatives is to co-exist and help each other. But as bigger entities try to swallow the smaller ones, the basic idea of establishing cooperatives stands defeated.”

Photo: Digo Bikas Institute

Across Nepal, our partner Digo Bikas Institute (DBI) is working to build a ‘post carbon society’.

DBI has supported communities such as Dhapsung (pictured here) to set up community-controlled solar panels.

Photo: Ashlesha Khadse

Dhapsung is a remote mountainous community which only recently built a road. The road brings both opportunities and some threats.

In collaboration with WACN, Digo Bikas invited them to support the formation of a women’s group in Dhapsung.

Pictured above is the Dhapsung women’s group.They have regular meetings and have articulated their own collective goals. Currently they are working on pooling resources and creating agroecological income generating activities. The women were shy and hesitant to speak at first, but revealed to us that they are only now getting used to publicly expressing their thoughts.

Photo: Ashlesha Khadse

Digo Bikas Institute is not only working in rural areas, it is also going into the heart of urban centers like Kathmandu. Pictured here is Kilagal, a historical neighborhood that was knocked down during the devastating earthquake of 2015.

Along with several allies, DBI is working to turn the area into a car free, bicycle zone. They succeeded in bringing about a similar ruling in part of a major tourist area called Thamel.

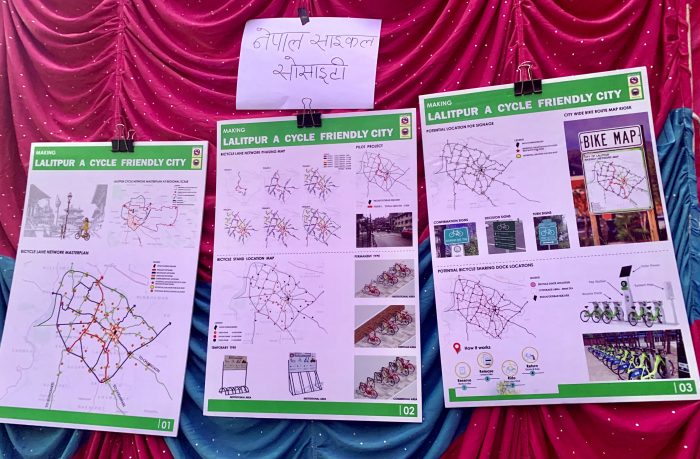

Photo: Ashlesha Khadse

Pictured above is a display by Digo Bikas Institute at a local festival that was organized by the community of Kilagal. The display showcases proposed maps of how Lalitpur (or the historic city of Patan) can be converted into a cycle friendly city.

Related Stories

Asia and the Pacific