Claiming of communities’ indigenous and inherent wisdom often means un-learning what has been decimated by dominant, imperialist narratives. So last month following the Thousand Currents Academy, our staff jumped at the opportunity for María Estela Barco Huerta to teach us about what’s needed to build individual consciousness, work collectively, and to take a more expansive view of global solidarity.

The following words in italics are gathered and paraphrased from María Estela’s translated presentation to the Thousand Currents staff. Thanks to Katherine Zavala, former Director of Programs, for the inspired, and grounded, and heart-full translation.

Ch’ulel, or spirit

“We start with the ch’ulel (espíritu). Everyone and every species has a spirit. Everyone has life. Tzeltal grandparents teach us to ask permission before we cut a tree down or build a house, etc. This makes me think about my duty to be in harmony with nature and others. If my spirit or heart is sick, or if I don’t recognize this in others, I cannot have a healthy life. It’s very important to wake up our chu’lel. Because life is hard.”

Stalel, or way of being

“Stalel (un modo de ser) is present in every community. There are two interpretations – the size of one’s heart or strength of spirit, and the structure of the community and its customs. We are learning that customs can be changed if they are not a positive way of being, for example, why don’t men ever make tortillas?

“Stalel is sometimes used to justify practices, but ultimately stalel reminds us that the heart is at the core of everything. It’s where our pain, and our happiness comes from. In indigenous languages, asking, “O’tan, pusikal?” is the way of saying, “How are you?” What it means is, “How is your heart doing?” or “What is your heart saying?” Stalel reminds us that the heart feels and the heart talks. This is why DESMI’s founder always talked about putting our hearts in our work.”

Ich’el ta muk, or great respect

“Ich’el ta muk (gran respeto) means you don’t say “Hello, how are you?” with indifference. You greet people recognizing their dignity, their “bigness.” Everyone feels. They walk. They talk. This concept of the gran respeto encompasses also self-determination for women and what they want to contribute.

“Recognizing people in this way upholds the possibility of us supporting each other and our development as human beings, and in people’s relationship with Mother Earth. Mother – she takes care of us – gives us everything we need for survival, so there is no individualist approach to work. It is all about the responsibility of being part of family and community. If I want to see the people I work with to develop themselves in a complete way, then I have to see the social change [needed] and transform the system.”

Lekil kuxlejal, or a good life

“Lekil kuxlejal (el buen vivir) is like a little plant. It’s a life you have to take care of over its whole journey. This is the same with people. When communities can develop health, education, self-governance, agroecology and food sovereignty without aggravating nature and the environment, then we have the complete panorama about what ‘buen vivir’ is all about.”

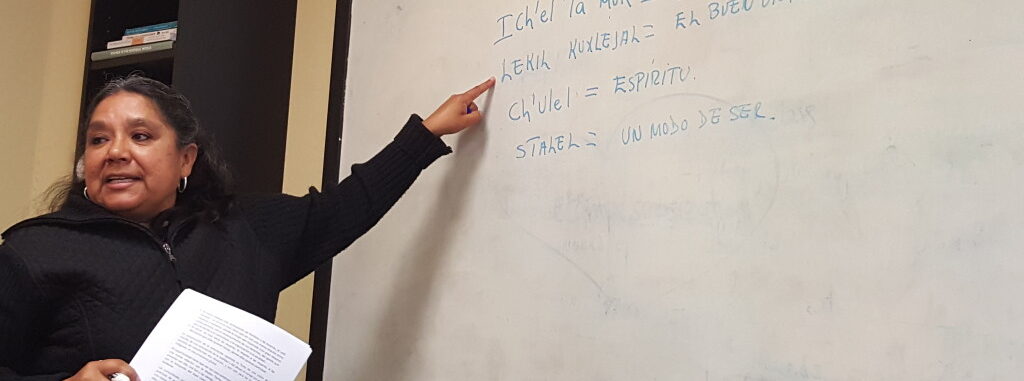

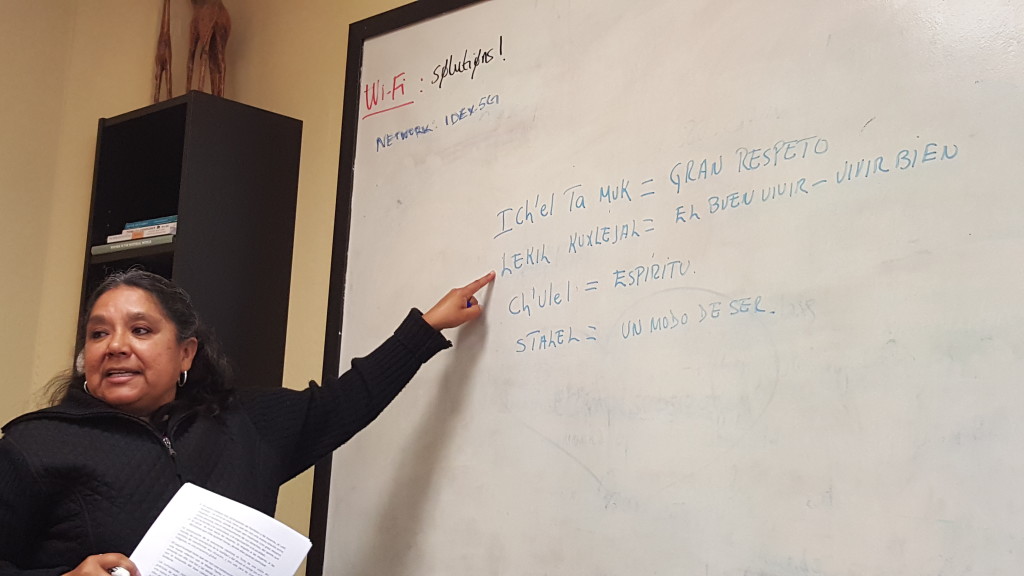

María Estela Barco Huerta leads the Thousand Currents staff in a “Buen Vivir” workshop in their offices.

María Estela shared that these indigenous concepts are another way of seeing the world outside of the current system. When everything becomes commoditized under capitalism, the system can become destructive, focused only on reproducing itself. And then when communities are not in harmony, collective work suffers because people’s spirit is being affected by negative energy.

María Estela challenged us to think about decolonizing our minds as the homework of everyone, not just indigenous people.

“We shouldn’t get used to being poor, marginalized. We have to recuperate our spirit, or ch’ulel, which is our strength,” she said. “We have to be kind to ourselves to decolonize our minds, [but] being kind and simple is the way to learn from the other person. Every day I can learn something.”

María Estela also highlighted DESMI’s work with autonomous municipalities [Good Governance Councils in Chiapas formed by the Zapatistas] shows that these indigenous concepts are part of how they are structured. These councils work collectively from ich’el ta muk in that each person contributes what they know, without large amounts of financial resources, based on their responsibilities to each other.

“They put heart and spirit in everything they do,” María Estela explained. “When one takes a responsibility, it is about what I have to learn. If I take care of that plant, it will grow.”

“As communities are fighting, making the effort to overcome oppression, we fall in love with them. My consciousness surfaced seeing how willing people were to show up and learn and fight together.”

Taking care of our responsibility to people, not in material terms, means that we are growing as people. That is our homework, to grow as people, to share our hearts with each other.

María Estela challenged the Thousand Currents staff to see the big “tarea” [homework] ahead of those of us in the United States – to form the political consciousness of people here.

“Here is where the policies are created that affect the world. It is important that people don’t become accustomed or paralyze themselves. We have to be able to feel other people’s realities, their suffering. It can’t be mechanical.”

There are many ways. Chains of solidarity can reach around the world and generate change within communities, where people can be people, living with dignity.