Lessons in Resilience: Meet the World’s Largest Indigenous Network

Part 1: Here We Go

“Be prepared for hazardous air,” my colleague messaged. “I got us extra masks.” Coming from the Pacific Northwest, where I’ve grown accustomed to hazy orange skies for weeks during “fire season,” I felt eerily prepared. From wildfires to floods to drought, climate change has meant that many of us around the world are experiencing a new normal in some way, shape, or form.

A view from the hotel in Jakarta. The sun peeks through the thick smog.

Three flights and 28 hours later, I arrived in Jakarta, Indonesia. Led by our Regional Director for Asia and the Pacific, Ashlesha Khadse, and our Program Manager, Rachel Arinii, I would embark on a five-day journey to immerse myself in the work of our movement partner Indigenous Peoples’ Alliance of the Archipelago (AMAN). Currently, 2,565 Indigenous communities, representing 22 million people, have joined AMAN, making it the largest Indigenous network in the world.

Part 2: The Sprawling City

As much as I was mentally prepared for the smog, I wasn’t quite ready for Jakarta’s infamous traffic. Bumper to bumper, three hours later, I arrived at the hotel in the capital neighborhood, Bogor. While traffic plays a major part in Jakarta’s severe air pollution problem, it’s the expansion of coal-fired plants that is most responsible. The good news, however, is that AMAN is playing a major role in organizing against these types of industries that pollute, destroy biodiversity, and infringe upon Indigenous rights and territories.

Welcome snack bowl of fruits endemic to Indonesia.

After a day of getting settled in, Ashlesha, Rachel, and I set out to visit AMAN at their headquarters in Bogor. As we gathered around the table, we heard about our movement partner’s multipronged approach to empowering Indigenous communities across Indonesia, which includes economic empowerment, membership and movement building, communications strategies for visibility, and political mobilization and advocacy.

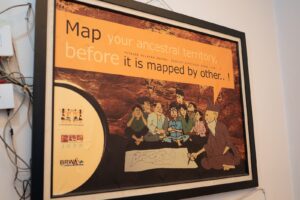

In the coming years, they aim to expand their renewable energy initiatives, launch Indigenous-led funds, and strengthen their mapping initiatives. Mapping plays an instrumental role in the protection of Indigenous peoples’ ancestral lands and often serves as a crucial first step towards recognition, which helps prevent land grabbing of Indigenous territories.

A poster at AMAN’s headquarters spotlighting the importance of mapping ancestral territory for Indigenous peoples to maintain territorial rights.

To date, AMAN has supported the mapping of 20.7 million hectares of Indigenous territories, an area nearly twice the size of Java. With AMAN’s organizing power, the number of local regulations supporting Indigenous rights has increased from two to 159. In addition to the 20.7 million hectares of Indigenous land mapped through participatory mapping, AMAN has succeeded in getting 3 million hectares of Indigenous land recognized by the government. AMAN has also launched over 80 Indigenous schools led by Indigenous youth.

Ode Rakhmann, Interim Managing Director of the Nusantara Fund, an arm of AMAN, describes the fund’s ambitious vision.

Next, we hopped into a van to visit one of their Indigenous-led economic justice initiatives, Gerai Nusantara. During the pandemic, AMAN launched a large Indigenous-led social enterprise with an online store. We visited their retail outlet shop in Bogor, which serves as a multifunctional space that holds a cafe supplied with Indigenous-grown coffee from the country, along with traditional crafts and textiles from villages across the archipelago.

Ashlesha Khadse with Rena, the manager of AMAN’s Indigenous collective of crafts and coffee, Genus Cafe.

Despite AMAN’s impressive progress, many Indigenous communities still lack legal recognition of their territories, making them susceptible to land grabbing. Indigenous peoples are increasingly threatened by weak protection, and by the Indonesian government’s lack of recognition of Indigenous rights.

In addition to supporting Indigenous economic initiatives, AMAN has launched their Nusantara Fund to provide direct funding mechanisms for Indigenous peoples’ efforts and initiatives in protecting and managing their lands, territories, and resources. Indigenous communities are at the frontlines of environmental conservation and are the largest contributors to preserving the world’s biodiversity.

Rachel Arinii and Eustobio Renggi, the Secretary General of AMAN, look out at the customary village of Tenganan.

Part 3: The Jungle

Our journey would now continue to Bali as we connected with communities that are part of AMAN’s network.

Bali is an island in Indonesia known for its iconic terraced rice paddies, beautiful beaches and coral reefs, forested volcanic mountains, and thousands of temples. Every corner is teeming with life. You might even have a run-in with some monkeys. One thing you’ll notice right away are the aromas that permeate the air: plumeria flowers, jasmine, incense. With each new day, Balinese offerings called canang sari—small baskets made of woven palm leaves that are filled with flowers, rice, and other symbolic items—are placed throughout the region. There is a palpable sense of life, in all its forms.

A view from above the terraces of Tenganan village, photographed with a drone.

We continue our journey to the customary village of Tenganan, a potential new partner in AMAN’s network. The Tenganan area is a sprawling 917 hectares of prosperous forest and farmland, managed by the main village (Desa Adat Tenganan Pegringsingan) and its community of around 760 people, with collective land ownership based on customary law.

Members of the Tenganan village, including youth and elders, give a presentation on their strengths and challenges.

In 2007, they launched their own Indigenous community-led renewable energy initiative through hydropower. In the past few years, more and more resorts have been built upstream by national and global investors, leading to land grabbing and water grabbing. As a result, Tenganan’s water supply has declined drastically, impacting the ability of their hydropower system to generate electricity.

They estimate that only five more years of water flow is left for the hydropower to stay viable. As we head uphill to visit their rice paddies and the micro-hydropower station, I’m struck by the breathtaking greenery and shocked by just how far the water has already receded.

Due to water grabs from new resorts, the water table of the river that the Tenganan village has relied on for hydropower has greatly declined. Rocks and sediment are seen along the surface.

Part 4: The Mountain

On our final stop, we visit with AMAN partner Catur Paramitha, a collective of Indigenous coffee producers hailing from the Kintamani region in Bali. Located in the north of the Bangli district with an average altitude of 1,500 meters (4,920 feet), Kintamani is one of the highest areas of Bali and looks out to the active volcano of Batur mountain. An enchanting land above the clouds, it truly looks heavenly in every sense of the word.

A coffee farmer and member of the Catur Paramitha coffee agroforestry farm gives a tour.

Kintamani Arabica coffee, known as jempolan, is cultivated from premium coffee beans flourishing in an elevated terrain, approximately 1,200 meters (3,930 feet) above sea level. Catur Paramitha’s approach embraces traditional ecological practices rooted in agroecology, strictly adhering to organic farming methods. Employing rainwater catchment, natural terracing for irrigation, and companion planting techniques for pest control, this coffee collective exemplifies a commitment to sustainable practices.

Coffee farmers and members of the Catur Paramitha coffee agroforestry farm.

The coffee agroforestry farm, a joint effort owned and operated by local communities in the Kintamani region, serves as both a direct source of income and a catalyst for locally driven land management and Indigenous-led conservation efforts.

A view from above Catur Paramitha’s coffee agroforestry farm.

This journey has been more than a physical one; it has been a journey into the resilient spirit of Indigenous communities, their deep connection to the land, and the collective power that fuels their fight for environmental justice. As I leave Bali and return home, I’ll forever hold with me deep respect for collective Indigenous power, the resilient spirit of the land, and the continuous pursuit of environmental sustainability, painting a canvas of hope and change.

Stay tuned for our upcoming photo essay featuring AMAN.

Rachel Arinii, Asia and the Pacific Regional Manager; Ayse Gursoz, Communications Manager; Ashesha Khadse, Asia and the Pacific Regional Director; en route, returning from Catur Paramitha’s coffee agroforestry farm.

Related Stories

Asia and the Pacific