Listening From The Head and Heart: My Take Aways From the Thousand Currents Academy

Guest Post By Christen Dobson, Program Director, Research and Policy, International Human Rights Funders Group (IHRFG)

We began with a story – that moment when our political consciousness was born; why we chose to advance social justice; the most formative experiences in our personal journey. Each experience we shared, each challenge we disclosed, brought us closer to one of the most important takeaways from the Thousand Currents Academy: the importance of building community.

We began with a story – that moment when our political consciousness was born; why we chose to advance social justice; the most formative experiences in our personal journey. Each experience we shared, each challenge we disclosed, brought us closer to one of the most important takeaways from the Thousand Currents Academy: the importance of building community.

In June 2014 I had the privilege of attending Thousand Currents’ inaugural Academy, a week-long training in culturally competent social justice philanthropy. This Academy is designed to turn western-driven, dominant models of international development and philanthropy on their heads. By using methodologies created by activists and communities in the global South, the Academy challenges social justice and development practitioners to learn differently, and provides models and tools through which to do so.

A general principle of the Academy, for example, is that every participant is a teacher with knowledge to offer, not solely those tasked with “teaching” and “facilitation” roles. Another unique aspect of the Academy is that most of the faculty are grassroots practitioners from the Global South who share from their lived experiences, rather than solely theory and textbooks. The Academy is one answer to Thousand Currents’ learning from its partners that “influencing the practice of social justice giving” is a key way in which Thousand Currents can utilize its privilege and power to create a more just and equal world.

A general principle of the Academy, for example, is that every participant is a teacher with knowledge to offer, not solely those tasked with “teaching” and “facilitation” roles. Another unique aspect of the Academy is that most of the faculty are grassroots practitioners from the Global South who share from their lived experiences, rather than solely theory and textbooks. The Academy is one answer to Thousand Currents’ learning from its partners that “influencing the practice of social justice giving” is a key way in which Thousand Currents can utilize its privilege and power to create a more just and equal world.

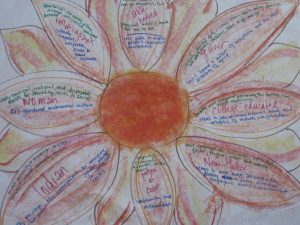

At the Academy, we spent five days collectively exploring the impact of our privilege based on class, race, gender, sexual orientation, and nationality; questioning contemporary models of philanthropy; and most importantly, listening to one another. The Academy challenged us to engage with our assumptions, perspectives, and discomfort. We grappled with questions such as:

- What do we lose when we experience privilege?

- What does it look like to leverage all of the resources at your disposal?

- What narratives do we believe need to be re-framed and what is philanthropy’s role?

- What assumptions do we want to unlearn?

- How can community assets, rather than needs, inform our philanthropy?

- How do we ensure that our institutions regularly ask themselves the tough questions about what is working and what is not?

- When we determine that a grantee’s work isn’t as effective as it “should be,” what perspectives are we using?

One of the most significant lessons for me was about space. Fire, a poem by Judy Brown, which we read together, asserts that it is the space between the logs of wood that makes a fire grow, not a greater number of logs. In fact, without creating openings between logs, the fire will fade away. As Brown says, “it is the fuel, and the absence of fuel together, that make fire possible.”

One of the most significant lessons for me was about space. Fire, a poem by Judy Brown, which we read together, asserts that it is the space between the logs of wood that makes a fire grow, not a greater number of logs. In fact, without creating openings between logs, the fire will fade away. As Brown says, “it is the fuel, and the absence of fuel together, that make fire possible.”

This poem was a powerful reminder for me of the critical importance of creating space – in my work, relationships, activism – and the need to step back, reflect, and lay each “log” with intentionality, rather than focus solely on productivity.

How does our focus on the “logs,” whether they are deadlines, dockets, indicators, negatively impact our grantees and the movements we support? How does our work to advance social justice suffer when we don’t take the time to collectively reflect? What do we stifle — innovation, spontaneity, the vitality of the movements — when we become consumed with “piling on logs”?

With the prevailing development paradigm largely focused on deadlines, deliverables, and measurable impact, it was refreshing to have an opportunity to approach development and social justice work holistically, centered on the value of reciprocal learning. I left the Academy feeling better able to responsibly practice solidarity and participate in a larger community committed to advancing social justice solutions that originate from the grassroots.

FIRE

Judy Brown

What makes a fire burn

is space between the logs,

a breathing space.

Too much of a good thing,

too many logs

packed in too tight

can douse the flames

almost as surely

as a pail of water would.

So building fires

requires attention

to the spaces in between,

as much as to the wood.

When we are able to build

open spaces

in the same way

we have learned

to pile on the logs,

then we can come to see how

it is fuel, and absence of the fuel

together, that make fire possible.

We only need to lay a log

lightly from time to time.

A fire

grows

simply because the space is there,

with openings

in which the flame

that knows just how it wants to burn

can find its way.

Related Stories