Power to the People: Kenyan Land and Environmental Defenders Triumph Through Challenges

Founded in 2009 and a Thousand Currents partner since 2023, Center for Justice Governance and Environmental Action (CJGEA) works to protect and advance the human and environmental rights of Indigenous communities affected by industrial extractivism and chemical pollution. CJGEA works across Kenya’s 47 counties, filing public interest litigation, delivering educational training, and mobilizing public protests and media campaigns. Among many achievements, the organization has been recognized for leading the campaigns that shut down 17 toxic sites and smelters across the country.

Phyllis Omido is one of the co-founders of CJGEA. Her tremendous leadership and tireless work have received international recognition: she received the Goldman Environmental Prize in 2015 and the Right Livelihood Award in 2023.

We spoke with Phyllis to dive deeper into the lessons she’s learned in community organizing, the origins of her activism, and how she sustains a vision for justice for the long-haul.

The interview was conducted by Deepa Ranganathan and transcribed by Fiona Teng.

What drew you to the fight for environmental justice in your community?

I’m from the western side of Kenya, but I live on the coast. I grew up in the rural areas, and my mother and father were both teachers. When you’re raised in the rural setting, you don’t buy fruit, you eat fruits from the trees; you don’t buy eggs, you keep chickens in your house. You wake up in the morning, go into the farm, and your children will have food. You do not understand the joy of such a lifestyle until you have lived it. That’s how I grew up.

So coming from that kind of environment, it was absolutely unacceptable to me that people, especially children, should have to live under huge dark, smelly smoke, day and night. I was quite shocked when I learned that some people have to pay a price to get basic access to clean water, air, and food. Why should any human being be forced to live in such circumstances? People in power expected the affected communities to just accept and live under such conditions and not raise any resistance. I cannot passively accept that.

You won the Goldman Environmental Prize in 2015 for your brave advocacy and grassroots organizing, which led to the shut down of a toxic battery smelter in your community. How did winning the award impact CJGEA and the communities it serves?

Immediately when I came back [from the award ceremony] I had one community meeting. I was expecting maybe 100 people. I got around 600 people attending the meeting! There was a lot of hope. Then I got a call from the Senate, and they informed me that they were ready to open investigations because I had put in a petition some time back, and I was pushing them to come to the community and listen to them.

So the award came with a lot of positivity because once the recognition had gone out and the issues were being articulated at the international level, our community members and politicians somehow felt obligated also to act. It opened a lot of doors.

“At the end, as you go on, one hundred percent of the community comes and stands with you because they witness firsthand what is happening.”

International recognition helped a lot in terms of advocacy, in terms of protection as well. Just before this award, my community meeting had been violently dispersed by the police, and they told me that they had instructions that I will never, ever hold a meeting in that community.

But of course, after I went for the award, and there was all this international hullabaloo, and local Kenyan hullabaloo as well, I went and had my meeting in the community and not even one policeman showed up! This is the power of advocacy, the power of international recognition, and I really appreciate and understand it’s a privilege.

Over the years of your grassroots organizing, what have you noticed in the level of political awareness and understanding across the communities CJGEA serves?

It’s not easy! When I started working in [my community] Owino Uhuru, some of the community members were defending the smelter because they were employed there. We got very strong resistance, especially from the men. The women, from the outset, were with me because they were telling me what they were seeing: the water was tasting different, the children were coughing. The women could see the health impacts of the pollution. But the men, they were getting paid, they were getting jobs, so it was very difficult [to convince them]. It’s never easy when you start a movement.

When I first began [to organize against] plans for a nuclear plant in Uyombo, there was a section of the community that was [resistant]. I had about 70% of the community with me. But there was the 30% saying, “We’ll sell our land at double its value.” I was telling them, “No! Not if they’re going to put a nuclear power plant in the middle of a marine park, or between the marine park and the Arabuko Sokoke forest.” I was telling them that their way of life was going to change, they wouldn’t be able to fish, they wouldn’t be able to grow their coconuts.

Now, in Owino Uhuru, I have 100% of the community behind me because they have already witnessed, over time, what I was telling them. I’ve been there with them as they buried the children that died. They have seen how the women suffered. The repercussions of an unhealthy environment are so visible. At the end, as you go on, one hundred percent of the community comes and stands with you because they witness firsthand what is happening.

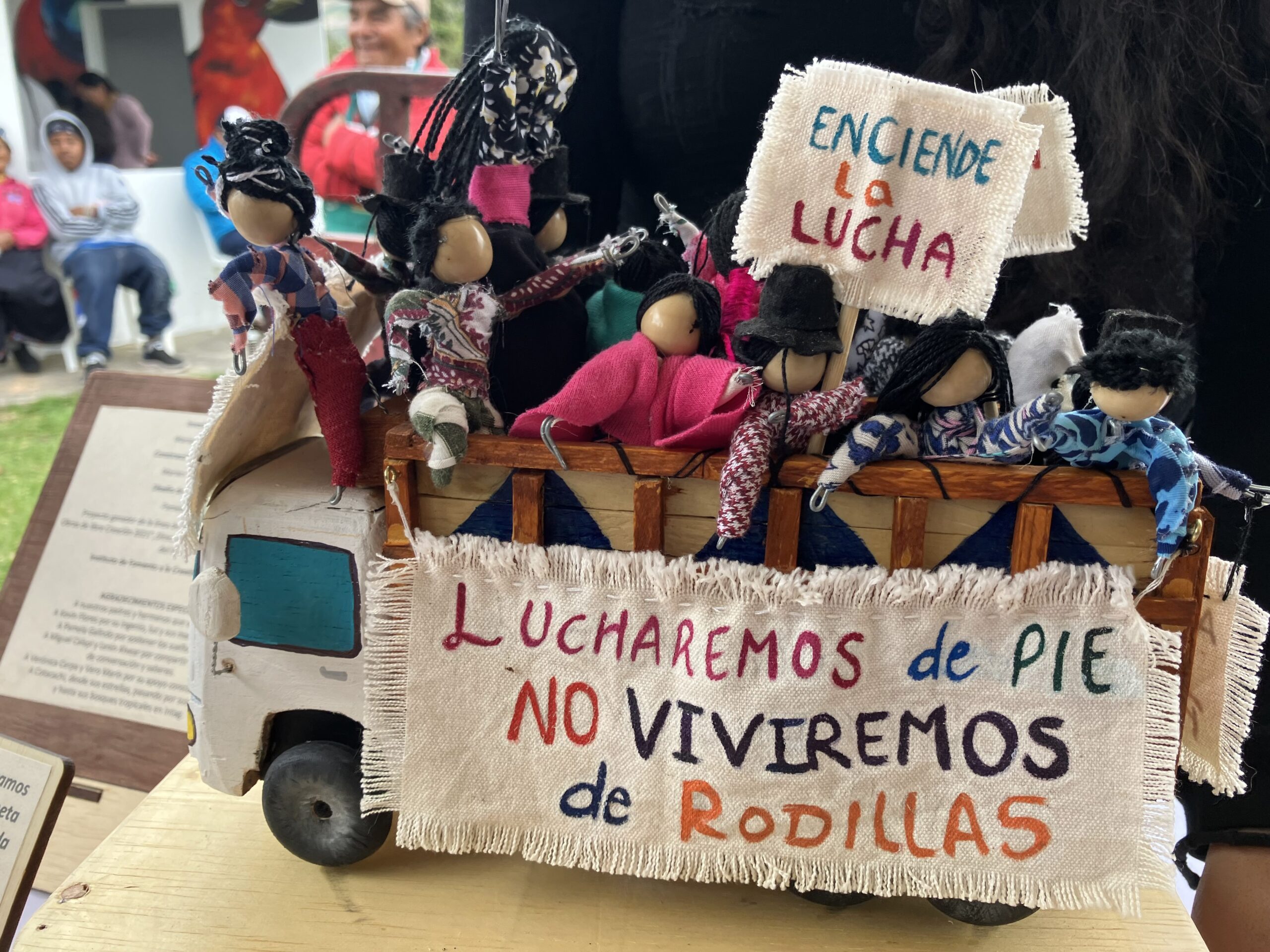

CJGEA organizing with the Uyombo community

In 2020, the court ruled in your favor, awarding $12 million USD to those affected by the lead poisoning in Owino Uhuru, but in 2023 we saw a blow from the Court of Appeal overturning this compensation. From your perspective, what happened?

[With regard to who would be responsible for damages], the Court of Appeal said they didn’t know who should be responsible for what portion, and that we should go back to the Environment and Land Court to decide who should pay what! You can’t give people compensation and then refuse to tell them [how it would be distributed]. This was a very corrupt judgment.

The other thing is the Environment and Land Court had given my organization $7 million USD to clean up the community and ensure that all the lead is removed from the houses, from the river, the soil, the roof, everywhere in the environment. The Court of Appeal said that they have given this responsibility to the National Environmental Management Authority (NEMA). NEMA is one of the [players who appealed our] case, so how can you tell them now to go ahead and clean the Owino Uhuru community? The Court of Appeal was very mischievous.

“People in power expected the affected communities to just accept and live under [poor] conditions and not raise any resistance. I cannot passively accept that.”

With our partnership with Thousand Currents, we put together a team of environmental lawyers from different organizations, and they agreed with me that we need to appeal the case to the Supreme Court. Our case was very strong, very straightforward, there was enough evidence. So we put our case to the Supreme Court, and they agreed to listen to our case.

When the case was supposed to start, we found that the government had not filed their documents yet. They said that it was because they realized that their lawyers were weak so they wanted to get external lawyers. For me, this is just delay tactics. The government has the best lawyers. You can’t say that Phyllis has better lawyers than the government! I don’t think that even if they acquired the best lawyers, that they would have a chance. Our case was solid!

Advocacy, strategic litigation, and other CJGEA areas of work are hard work. And they are long-term work. Things don’t change overnight. What motivates you and your organization to still keep fighting the fight knowing that the results are not going to be immediate?

I always say that if anyone had witnessed what I witnessed, they would not easily give up.

[I have seen] children dying, children that I’ve seen growing up in the community, succumbing to lead poisoning. I have seen young women, 24 years old, [have] so many miscarriages, until their wombs are eventually removed and they can no longer have children because of their high lead levels. The government tested the Owino Uhuru community and they were shocked at the levels that they got: up to 420 micrograms per deciliter. (At the time, the World Health Organization defined lead poisoning at five micrograms per deciliter.)If anyone witnessed it, they would not let go of someone rubbishing [their] case and saying that the community does not deserve justice. I’ve been told not to see black and white too much and try to see gray, but for me it’s black and white. It’s not something that has any gray in it. This community was polluted and they have to be compensated. So we’ll present the case, we would win the case, and that would be open and shut.

At the beginning, it looked like it, because the Environment and Land Court actually did everything that we asked. It awarded the whole community compensation. I never at one time thought that someone would actually think of appealing against this judgment! What really shocked me was the fact that the state agencies, NEMA and the Export Processing Zones Authority (EPZA), went to court to appeal this case.

Sometimes I feel really discouraged. When someone passes on, you get that call and they tell you so-and-so has died. It really breaks you because I don’t carry these cases on for me. I carry them on for the communities, especially for the children. And when the children that you’re fighting for die, it kills something in you, and it breaks something in you.

But I set out to get justice. For me, it’s justice and nothing else. So I have to keep going until what I set out to do is achieved.

CJGEA participating in the Just Transition Energy Conference

I know that it’s hard to be a female movement leader. Can you tell us a bit about how your gender has affected your organizing?

I think I was a feminist from the time I was born because I came from the Luhya community, which has norms and traditions that try to put women in their place. Where I grew up, it’s not a woman’s thing to climb trees, but I was the number one champion of climbing trees in my village! There’s a certain part of a chicken that you’re not allowed to eat in my community, I was the number one person to taste and see why, what would happen if I eat this part of the chicken. Of course I used to get whipped a lot! I used to get beaten a lot in my family because I always tested those boundaries that were put there; [I wanted] to understand why women were relegated to a certain place in the society.

Growing up, my father was very violent. From a very young age, my mother was beaten up [a lot]. So I grew up always trying to protect my mother, and I think from this, I became a very strong defender of women.

“Women carry a movement very well.”

The first time that we got the Assistant Minister of Environment to come to Owino Uhuru, the first thing he said was, “this woman, does she have a husband? She doesn’t have a husband! She is a single mother!” I learned very early on that I would be picked on because I’m a woman.

There was that one time I was attacked by a group of men, when they were beating me outside my house, accosting me, they told me, “you think you’re a man, you want to stand up against men in this society!”

But I carry my head very high and very strong, and I believe being a feminist has helped me a lot in my movement, in my strategizing, in mobilizing, especially the women. If you look at the pictures of my meetings, more than half of them are women. Women carry a movement very well. I’m very grateful for that.

I’ll continue to fight for my place in this society because I now have a daughter and she should know that she has equal rights as well. I keep training her that every human being is born free and equal, in dignity and with rights. She needs to grow up knowing that.

Editorial note: In December 2024, the Supreme Court of Kenya issued a landmark ruling awarding the Owino Uhuru Community a total of 1.3 billion Kenyan shillings (approximately $10 million) as reparations for loss of life and personal injury caused by the setting up of a lead acid battery recycling factory in its surroundings.

Related Stories